After leaving Samaná at 8 am, we see some more whales from a distance on the way out. We are going straight into the wind (20-28 knots), which is the roughest point of sail for us; Matt says the first few hours will be tough. It feels like crossing the Albemarle Sound. There are 8-10 foot swells with a few waves that look to be 15 feet high. I duck down to get snacks and see that everything is all over the place. Things that are normally stowed fine are not ok today. Despite the 2-inch edge on the nav station, Matt’s charts are all over the floor; oranges and grapefruit have bounced out of their crate and are rolling around; Matt’s tool cabinet has flown open. Later, it starts raining and I go down below to avoid getting wet. I get thrown and land on my back on the cushioned bench at the table (Matt later says he

saw my feet fly up in the air before I landed). I start to get up and then think, I just landed on something soft. Why would I want to get up? I lie back down thinking maybe it will stop if I don’t move. Maybe I can click my ruby slippers together and I’ll suddenly be back in Kansas (or Ohio). It’s so loud. The perception of sailing is that it’s quiet but it’s incredibly noisy down below. Pots and pans and spice jars rattle in the cupboards. Imagine a giant picking up your house and shaking it. Every time the boat comes crashing down on another wave, it sounds like we land on something hard. The rain passes and I shakily make my way back on deck. I emerge, wide-eyed and with windblown hair yelling, “Stop the bus! Stop the bus! I want to get off!” Matt laughs. I’m only half-joking. It gets a tiny bit better once we round the northeast corner of the DR but never really settles down.

Around noon I go down to prepare lunch. It’s kind of like being in a washing machine (not that I’ve ever actually been in one). Because I’ve convinced myself I never get seasick, I stay down below far too long picking up things from the floor. I start to get a headache and wonder if it’s seasickness. I quickly lay down and close my eyes but it’s not helping. I have lunch on the stove but bolt past it as I race up the companionway. Matt sees my face. He points to the edge of the cockpit and tells me to sit and stare at the horizon. That’s not helping either. I can’t believe this, I’m thinking, I’m actually going to throw up. I do NOT throw up! Famous last thoughts because my body clearly disagrees with my mind. I lean over the edge and begin retching so violently that I’m positive my eyeballs are going to pop out of my head. I hear the boys gasp because I am known for my stomach of steel. After a few minutes of making a spectacle of myself, Joshua’s small hand begins patting my back. Once it’s over, I feel 100% better. Within two hours Malachi also throws up. After a bit, we get some food and liquids into him and he also recovers. Later that afternoon Joshua says, with some pride, that he and Matt are the only ones who haven’t thrown up. I say that, if he hurries, he can beat Matt and come in third place. He gives me a puzzled look. “Joshua,” I say, ‘today is the vomit contest. I won the contest and Malachi came in second place.” I tell Malachi to give me a high five. He is laying on the deck under strict orders to keep his eyes closed. He weakly waves his hand in the air and I give him a high five. Joshua rolls his eyes.

More hours pass and I serve dinner on deck. Matt brushes the boys’ teeth and helps them to bed because I’m still a bit unsettled by my stomach’s violent rebellion. All of a sudden I hear Matt yell, “I need some help down here!” He had put Malachi into his berth with explicit instructions to lay down and keep his eyes closed. Ever the doer (gee, wonder where he gets that from), Malachi opened his eyes for a minute or two to rearrange his stuffed animals. That’s all it took. He vomited all over the floor, Matt’s arm and on his pillow and berth cushion. Matt managed to catch the rest of it in a bucket. After quickly mopping it up as best he could, Matt comes on deck and, to his credit, says “I think we just need to be in the moment. At least it’s not boring.” Yes, I agree, vomit is rarely boring.

The boys are finally tucked in their berths and Matt says he is tired also. I tell him to sleep and that I’ll be on watch from 8 pm to midnight. He gives me clear instructions to get him if anything out of the ordinary happens. Every 10 minutes I check the wind speed and direction, the chartplotter, the sails and look all around for other vessels. There’s been no one else on the chart for two hours when a boat pops up out of nowhere. I check its AIS info and see that it’s a tanker, 625 feet long and 92 feet wide. It disappears from the chartplotter again but I still don’t see it physically anywhere around us. It’s getting closer and not being able to see it, either on the chartplotter or the ocean, freaks me out. Storm clouds have been approaching and a squall hits. The winds increase to 30 knots with gusts up to 39 and the rain comes. I’m soaked. The wind doesn’t seem like such a big deal and I adjust our course to compensate for it. The hatch flies open and Matt is standing below. He looks frazzled and asks what’s going on. I update him and say the winds have died down to 8-12 knots and we’re probably in the eye of the storm. His eyebrows raise when he hears the wind meter hit 39 knots and I didn’t get him. He is not pleased. “What’s your plan?” he asks. My plan? What plan? I didn’t know I needed a plan. Isn’t the plan to just keep sailing? “My plan for what?” I respond. “For when the other side of the storm hits us,” he says patiently. “Uh, … I’m not sure I have a plan,” I confess. “Exactly,” Matt says, “This is why you need to wake me up.” He goes on to explain how the boat loses steerage when there is low wind and that, if a huge gust hits us broadside, it could slap the boat down into the water. Hmm… good to know. If we turn on the engine, at least we will have steerage and can turn the boat into the wind. I’ve learned just enough to be dangerous but not enough to know that I’m dangerous. Perfect.

We arrive at 8 am the next morning at Ocean World Marina in Puerto Plata and again go through customs and immigration. Ocean World is one of those places that probably began with high hopes that don’t seem to have been realized. It’s still a nice place and a great reward after a long passage. While checking in at the marina, we find that they have two small apartments for rent for only $60-80/night. Hmmm… vomit-smelling, salty boat or clean apartment. Easy choice. We spend one day resting and the next day cleaning the boat and getting ready to go again. Two nights in an air-conditioned apartment with a real bed and bathroom are heavenly.

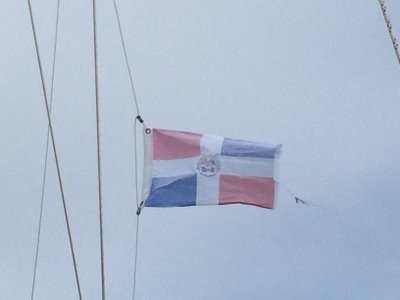

On Tuesday, March 3 we are ready to go again. Although it goes against the rules, the customs official offered to check us out the night before so we could leave when we wanted. He learned that my Spanish came from living in the DR for two years and said I was now a daughter of the country. There was a long story about his several maladies and those of his father. I wasn’t sure if they were an effort to connect or the prelude to another bribe. Just to be safe and ensure we could leave the country, we give the money. In the morning, the commander and the intelligence officer come back on board. The commander is easy and less imposing than the one in Samaná. He does the paperwork as the intelligence officer walks through and inspects the whole boat. He knocks on the mahogany ceiling every few feet. “What are you looking for?” I ask in Spanish. “Narcoticos,” he replies. “How would you know if they are there? Are you listening for something in the space?” I ask. “Si,” he says. Hmmm… good to know. Note to self: If we ever decide to traffic drugs internationally as a family, don’t hide them in the ceiling. We are now experts at bribing government officials and hand over the cash without even blinking.

[PS. My Word symbol function is not working so some words that should have accents don’t. Just so you know I’m not being lazy]